Insights from Annes Mboya, nurse-midwife at Kakuma Refugee Camp

On June 20th, the international community observes World Refugee Day, a day to highlight the voices of the approximately 80 million people, including women and children, who are forced to flee their homes because of violence, war, persecution, or natural disaster, as well as those who serve them. Around the world, midwives, nurses, community health workers, physicians and health care professionals devote their lives – and sometimes risk their safety – to deliver quality, lifesaving care to mothers and newborns.

Globally, 2.5 million babies die during their first month of life and an additional 2.6 million are stillborn, with many of these occurring in crisis settings. The scale is overwhelming: in 2018, approximately, 29 million babies were born into conflict-affected areas, and an estimated 500 women and girls die from complications of pregnancy and childbirth every day in humanitarian settings. In times of crisis, mothers must overcome immense obstacles to provide care and safety for their children, and particularly newborns, even while their own vulnerability to poverty, malnutrition, sexual violence, unplanned pregnancy, and unassisted childbirth greatly increases. To achieve SDG3, women and babies in the most vulnerable settings cannot be ignored – urgent action prioritizing lifesaving interventions and supporting health workers during humanitarian crises in required.

The IAWG Newborn Initiative (INI) was established last year to accelerate global preparedness and response to deliver high quality maternal and newborn health care, and to improve newborn health and well-being in humanitarian and fragile settings. The INI has a mandate to hold the global community accountable to progressing the priorities agreed upon within the multi-sectoral Roadmap to Accelerate Progress for Every Newborn in Humanitarian Settings 2020-2024. It operates through the IAWG MNH working group, and collaborates closely with both the ENAP in Emergencies working group and the Child Health in Emergencies and Humanitarian Settings working group to jointly advance an evidence-based agenda aimed at delivering a continuum of care across the life course. INI looks forward to partnering with AlignMNH to ensure stakeholders in crisis settings are engaged in future efforts on sharing, learning, and problem solving around priority issues for improving maternal and newborn survival and preventing stillbirths.

In honor of World Refugee Day, the INI spoke with Ms. Annes Mboya, a nurse-midwife working in Kenya’s Kakuma Refugee Camp, who shares her insights into the challenges faced by providers, as well as mothers and newborns, in Kakuma. Her passion and experience are representative of millions of healthcare workers around the world, and we call on global donors and stakeholders to ensure their voices are not left behind.

Learn more about newborn health in emergencies

Follow the IAWG Newborn Initiative on Twitter

Ms. Annes Mboya and her colleagues providing breastfeeding counseling to a mother, Kakuma Refugee Camp

Photo credit: Elsie Njambi

When a woman comes to the hospital walking, they should go home walking. If they came to the hospital with a baby in their tummy that was alive, they should go home with that baby breastfeeding.

Anne Mboya, IRC Nurse-Midwife

In fragile and humanitarian settings, an estimated 500 women and girls die from complications of pregnancy and childbirth every day (UNFPA, 2019).

Ms. Mboya’s decision to become a physician was driven by the loss of her uncle who battled with HIV/AIDs. Annes witnessed the stigmatization her uncle endured due to his disease, and she became committed to ensuring that no person would lack healthcare or face persecution because of their medical condition or background. She trained to become a certified nurse-midwife and has been advocating for quality care for patients ever since.

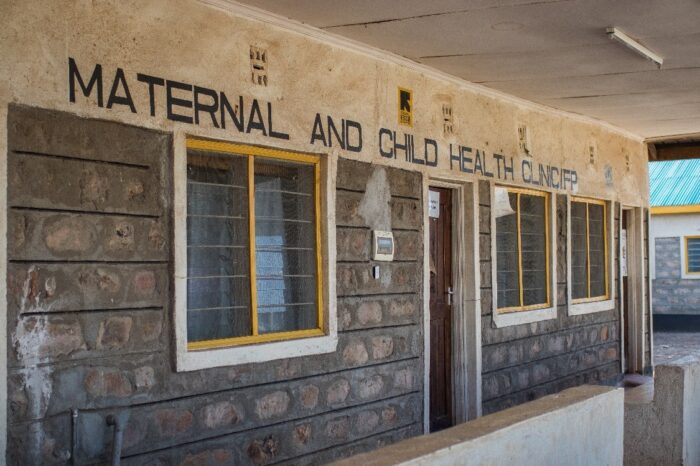

She currently works as a nurse-midwife at a referral hospital run by the International Rescue Committee (IRC) in Kakuma Refugee Camp. This facility serves clients from both the camp and local community, though a majority are refugees. Services at the hospital are free to all who seek care, including maternity, pediatrics, and gender-based violence (GBV), as well as outpatient, community follow-up, referral, and ambulance services.

“When you find that someone is not able to make decisions about their own lives, it is a major concern.”

The power of decision making is a key concern for mothers in Kakuma, and Ms. Mboya has frequently seen many mothers in her facility denied decision making powers, with decisions instead often made by a spouse, parent or other relative. Some women do not have control over the number of children they have, the method of family planning they use, whether to receive emergency care, or even what foods they can eat during pregnancy. This has led to a number of Ms. Mboya’s patients sneaking to the facility to seek these services. The COVID-19 pandemic has made this worse for many, as birth companionship has been limited and thus the decision maker is not always present. Ms. Mboya described cases where an emergency procedure, such as a cesarean section, was required but her colleagues had to race against the clock as they waited for the decision maker to be reached either by telephone or physically, putting the life of both the mother and the baby at higher risk.

Photo credit: Elsie Njambi

When asked about health risks for newborns in Kakuma, Ms. Mboya said, “we lose most of our neonates to birth asphyxia because we do not have the facilities to care for them. We do not have a newborn ICU, so they end up getting substandard care, in my opinion.” The nearest hospital with a NICU is in Nairobi, one hour and forty-five minutes by plane or ten hours by road. She also highlighted the connection between poor maternal nutrition and premature births, and emphasized the need for enhanced nutrition services for both mothers and babies in Kakuma. Additionally, her facility sees mothers who give birth prematurely due to domestic violence and trauma. In Kakuma, there is a center dedicated to providing gender-based violence (GBV) services, but the maternity department still sees a handful of these cases when the women go into labor. Ms. Mboya stressed that while these services exist and are utilized, she believes that due to fear of retaliation from the perpetrator, most cases go unreported.

“We end up losing babies for reasons we can easily prevent.”

Ms. Mboya and her colleagues do everything in their power to provide mothers and babies with the best care possible, but service delivery is impeded by challenges that are all too common to conflict settings. The staffing capacity at the referral hospital is limited and working overtime is common: Ms. Mboya’s department has 42 beds and oftentimes only one nurse is working on the floor. In addition to facility services, colleagues do door-to-door follow ups to ensure that both mother and baby are healthy and thriving. And as with many other health facilities around the world, the COVID-19 pandemic has not spared Kakuma; colleagues are missing out on the frequent and hands-on trainings that are required to maintain skills.

While she herself is not personally affected by security issues, some of the staff at the facility are refugees and have reported being attacked on their way to work. Language barriers are also a major challenge: while most patients can converse in one of a few common languages such as English, Kiswahili, and Arabic, Kakuma serves several tribes, and it is difficult for healthcare workers to learn all their individual languages. In addition, cultural differences add a layer of complexity to ensuring women receive the care they deserve. For example, some cultures do not allow women to undergo caesarean sections and/or believe that a woman who delivers through one is not woman enough. “To be treated humanely is the best thing that we can offer the refugees and people we work with.”

Photo credit: Elsie Njambi

On World Refugee Day, Ms. Mboya calls on donors, stakeholders, agencies, and actors to not give up on these mothers and babies. She stresses the importance of maternal and newborn health in these settings, saying “Mothers are the ones who maintain the continuum of care and by ensuring the health of a pregnant woman and her baby, you are ensuring continuity of life. These women deserve protection and care as much as any other person.”

While she applauds the work that has been done, she hopes for continued collaborations with providers in the communities to ensure maternal and newborn health is a priority in settings with the highest burden. “I would ask them to ensure that more funding is directed to this line of work. Mothers and babies are very susceptible to preventable illnesses and complications, and we need funding to protect them and keep them safe and healthy.”

Photo Credit: Kellie Ryan/IRC