Now is the Time to Use Digital Tools to Strengthen Pregnant Women’s Self-Care for Safer Pregnancies in LMICs

Imagine a world where every pregnant woman, no matter where she lives, has the tools and support she needs for a safe and healthy pregnancy. For many women in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), this vision is far from reality. Despite advances in medical research and public health like self-care opportunities, maternal deaths in these regions remain alarmingly high. So, what’s going wrong?

Why do pregnant women die in LMICs?

Countries worldwide are struggling to meet the Sustainable Developmental Goal of reducing maternal deaths to 70 per 100,000 live births. This is especially true for LMICs, especially in sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia. Traditionally, the focus has been on the direct obstetric causes of maternal deaths during pregnancy and childbirth, like postpartum hemorrhage and sepsis. But recent studies show that the preventable deaths of millions of pregnant women annually are not solely attributable to physical complications but also from prevailing social determinants of maternal health.

Social determinants of health encompass the conditions in which women are born, grow, work, and live before, during, and after pregnancy. Gender disparities, income, education, ethnicity, and race have been identified as strong predictors of death and disability during pregnancy, childbirth, the postpartum period, and beyond. Social determinants like these create a complex web of challenges that biomedical solutions alone cannot untangle.

Picture the story of Sheeba, a young woman we met during our research and outreach efforts in a rural village in Pakistan. Sheeba is pregnant with her first child and, like many women in her community, faces numerous barriers to access maternal healthcare. The village lacks a nearby healthcare facility making the journey to the nearest clinic long and arduous. Financial constraints further limit her ability to seek regular prenatal care. Cultural norms and limited education also play a role, leaving her unaware of the warning signs of complications like preeclampsia. After returning from the village, we learned that Sheeba and her baby died during the seventh month of her pregnancy. She experienced seizure activity and lost consciousness. In an attempt to save her and the baby, her family members rushed her to a hospital emergency in the city. The doctors performed an emergency C-section. After an hour or so, they announced the heartbreaking news of Sheeba and her baby’s deaths.

How can digital tools strengthen self-care agency and ensure safer pregnancies?

One effective way to tackle the social factors affecting maternal health is by empowering women and strengthening their ability and agency to care for themselves. The concept of self-care is defined by the WHO as “the ability of individuals, families, and communities to promote health, prevent disease, maintain health, and cope with illness and disability with or without the support of a health worker.” Self-care during pregnancy stands to improve the way antenatal care is provided, by expanding access to care, and catalyzing a fundamental and sustainable positive shift in how pregnancy care is provided. Self-care interventions has the potential to empower pregnant women as active partners in managing their own health. These interventions offer benefits such as convenience, cost-effectiveness, empowerment, and access to preferred options.

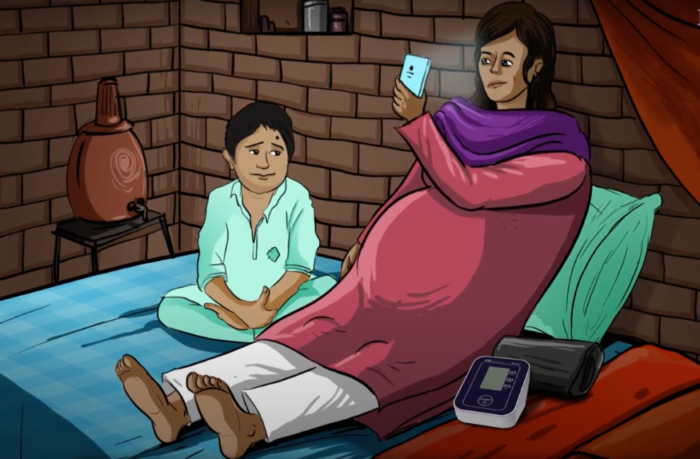

In our increasingly connected world, technology offers a promising avenue to enhance self-care agency among pregnant women in LMICs. Digital tools can serve as pathways for the uptake and adoption of self-care interventions such as self-monitoring of blood pressures, blood sugars, and recording symptoms. These self-care interventions can help overcome social determinants of health such as gender-based disparities in decision-making, limited access to education and healthcare, restricted mobility, and insufficient patient education. There are several examples of digital health solutions used to support pregnant women in LMICs, particularly aiming to empower and support them, thereby improving their self-care agency.

Some of these digital tools include:

- Mobile Health Apps can provide women with vital information about pregnancy health, nutrition, and warning signs of complications.

- Telemedicine can bridge the gap between healthcare providers and pregnant women, especially in remote areas. Virtual consultations allow women to connect with healthcare professionals without the need for travel, ensuring timely advice and intervention.

- Wearable Technology like smartwatches can monitor vital signs such as blood pressure and heart rate, alerting women and their healthcare providers to potential issues before they escalate. This continuous monitoring can be crucial in managing conditions like preeclampsia.

- SMS and Voice Messaging Services can deliver important health tips, appointment reminders, and educational content in local languages, reaching women even in areas with limited internet access.

A mobile app could help a woman like Sheeba monitor her blood pressure and other healthcare measures and symptoms at home, enabling real-time monitoring by healthcare providers and overcoming barriers such as restricted mobility, limited access to healthcare, insufficient patient education, gender-based disparities in decision-making, geographical distance from healthcare facilities, and a lack of reliable transportation.

What needs to be done now?

The global health community needs to prioritize self-care for pregnant women to improve pregnancy experiences, quality of care, and outcomes in LMICs. This can be achieved by leveraging digital tools that empower women and provide essential support throughout their pregnancies. Examples include:

- Expanding digital infrastructure by investing in improving internet connectivity, ensuring access to mobile devices, and providing reliable power sources in remote areas. These foundational elements are crucial for the successful implementation of digital health solutions.

- Fostering collaboration and innovation by encouraging partnerships between governments, healthcare providers, technology companies, and local communities to develop innovative solutions that address the unique challenges faced by pregnant women in different regions.

- Increasing education and training by educating women about the available digital tools, their usage, and benefits. Simultaneously, train healthcare providers to support and guide patients effectively in using these tools.

- Ensuring cultural relevance by developing digital tools that are culturally sensitive and linguistically appropriate. Engage local communities in the design and implementation process to ensure the tools are relevant and widely accepted.

Let’s join forces on #SelfCareDay and everyday to harness the power of digital tools to strengthen pregnant women’s self-care in LMICs. By investing in technology, education, and collaboration, we can pave the way for safer pregnancies and better maternal health outcomes, ensuring no woman is left behind. For Sheeba and millions of women like her, the integration of digital tools into maternal healthcare systems represents a beacon of hope.

Anam Shahil-Feroz (BScN, MSc, PhD) is an Assistant Professor at Western University and was an IMNHC 2023 Fellow.

Anum S. Hussaini (BScN, MS) is a Graduate Research Assistant at Harvard University.