Quality Medicines Matter: Quality-assured medicines are essential to achieve high quality maternal care

The need to prioritize access to quality medicines

While there has been significant global progress in reducing maternal mortality over the last two and half decades, there are still significant disparities between, and within, countries. The vast majority of the world’s maternal deaths can be prevented with access to timely, high-quality care and the essential medicines needed to address the leading causes of maternal mortality: postpartum hemorrhage (PPH), pre-eclampsia/eclampsia and infections. PPH – severe bleeding after childbirth – is the leading cause of maternal mortality worldwide – accounting for 20% of all global maternal deaths; 85% of all maternal deaths from PPH occur in Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia.

While the World Health Organization’s (WHO) quality of care framework focuses on ‘safe and effective provision of evidence-based maternal health care practices,’ including sufficient supply of medicines, it overlooks the quality of medicines as an essential component of quality care. Even the most skilled health care workers cannot save a woman’s life if they don’t have the right tools at their disposal – especially safe and effective medicines.

Access to affordable, clinically-recommended medicines that consistently meet quality standards is vital to help ensure better and more equitable health outcomes for women. Unfortunately, health systems, especially in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), struggle to safeguard the quality of their medicines. In fact, according to the WHO, 10 percent of all medicines in LMICs worldwide are substandard or falsified. Shockingly, when it comes to medicines that prevent hemorrhage, that figure rises to almost 50%. Nearly half of all medicines that are used to prevent or manage postpartum hemorrhage fail quality tests in LMICs – with life-threatening consequences for women. A recent study estimated that the economic cost of poor quality maternal medicines in Ghana is $18.8 million annually – showcasing the undue economic strain poor quality medicines puts on already financially vulnerable health systems.

To accelerate progress in reaching the SDG target for maternal mortality, it’s critical to take a broader view of what quality care means. Strategies to improve maternal health must ensure that medicines used during childbirth meet quality standards. That means assuring a product’s integrity across the value chain from bench to bedside – from confirming the quality and composition of its ingredients, adhering to Good Manufacturing Practices, labeling it for proper use, transporting and storing it appropriately, through to administering the product correctly to a woman to prevent and treat a childbirth emergency.

What is driving the quality challenges of maternal medicines: countries on the frontline

Nigeria

Nigeria has more maternal deaths than any other country in the world and accounts for 20% of global maternal deaths. One of the biggest challenges for the Nigerian health care system is protecting the safety and quality of its maternal health medicines. Approximately three-quarters (75%) of oxytocin and 33% of misoprostol – medicines used to prevent and treat postpartum hemorrhage – in Nigeria are below quality standards, putting women at unnecessary risk during childbirth. To maintain its effectiveness, misoprostol must not be exposed to humidity and moisture, and oxytocin requires temperature-controlled transportation and storage –very challenging requirements in hot climates with unreliable electricity and weak cold chain infrastructure.

Several factors contribute to the poor quality of maternal medicines in the country. For example, there is limited coordination and regulation of the supply chain at the state and federal level, including inadequate management of the importation, storage and distribution of medicines to ensure that they meet quality standards as they move through the health system to patients. In addition, pharmacy regulators do not have formal structures and lack the financial and human resource capacity necessary to report and remove substandard medicines from the system.

Poor dissemination and inadequate training on clinical guidelines and regulations related to safeguarding the quality of medicines have exacerbated longstanding issues with proper use and quality of oxytocin. As a result, fewer than half of health care providers in Nigeria are aware of how to properly store the medicine, and only 34% follow recommended storage practices in their health facility. On top of this, health facilities have frequent stock-outs of medicines and end up turning to the open market where the quality of the medicines they buy is especially difficult to monitor and regulate.

In 2022, Nigeria Health Watch – an advocacy organization – published a report highlighting the challenges and drivers of low-quality medicines in Nigeria’s supply chain system. The call to action report outlines recommendations to (1) change policies that would strengthen the local supply chain and increase access to quality medicines, (2) build the capacity of health care providers to ensure proper storage practices within health facilities, and (3) scale public-private partnerships to address stock-outs and quality concerns.

Rwanda

Researchers in Rwanda conducted a study in 2021 to assess the quality of medicines used to prevent and treat postpartum hemorrhage. They found that out of 10 medicine brands, the only products with quality concerns were those that did not have a WHO prequalification or were not manufactured in countries with rigorous regulatory systems.

Out of concern for patient safety, the country’s Food and Drugs Authority responded quickly and effectively. It recalled all medicines that fell within these two categories and removed substandard maternal medicine brands from the local health care market. Rwandan authorities recognized the need to strengthen regulation and enforcement of the qualifications required of maternal medicine suppliers and have implemented processes to ensure that substandard medicines never enter the country’s health care system.

It is notable that although Rwanda’s FDA was only established in 2018, technical assistance support from USAID has helped the Rwandan FDA make strong progress based on the WHO’s benchmarking tool for evaluating national regulation of medical product quality, safety and efficacy.

Bangladesh

Looking back to 2016, Bangladesh had challenges with regulation and a poor track record of implementing product management guidelines. As a result, a staggering 70 to 80% of all life-saving medicines in the country were considered counterfeit or did not meet quality standards. There were no oxytocin or misoprostol products available that met quality standards – a serious health threat to all pregnant women.

With support from USAID-funded Promoting the Quality of Medicines Program, Bangladesh succeeded in strengthening the capacity of its national drug regulatory body, the Directorate General of Drug Administration, and the National Drug Control Laboratory (NCL) to effectively (1) test drug quality, (2) report product concerns to manufacturers and (3) promote strong governance and regulatory practices. As a result, the NCL achieved WHO accreditation in quality testing for medicines in 2020 and is now one of only 55 WHO-prequalified quality control laboratories in the world – a huge leap in only a few years.

Moving forward

Similar stories of poor-quality medicines and efforts to address them can be told in many LMICs. As governments continue to work towards achieving universal health coverage and reducing maternal mortality by strengthening their health systems, they must focus on equitable access to high-quality care – including quality medicines that health providers and communities can trust.

The urgency to improve the quality of medicines is not a new issue in global health. USP’s The Medicines We Trust Campaign in 2019 raised alarm bells about the public health threat of substandard and falsified medicines and the need for universal access to quality-assured medical products, including medicines, vaccines and diagnostics. However, more concerted action is needed to address the complex vulnerabilities of health care systems and their supply chains if we are to make progress on maternal mortality. Here are immediate opportunities for action:

- Fund research to better understand how poor-quality maternal medicines affect women’s lives, health and wellbeing

- Analyze the increased cost that poor-quality medicines impose on health systems, especially those already financially constrained, to advocate for change

- Conduct country-level assessments to identify local health care system vulnerabilities and drivers of poor-quality supply chains

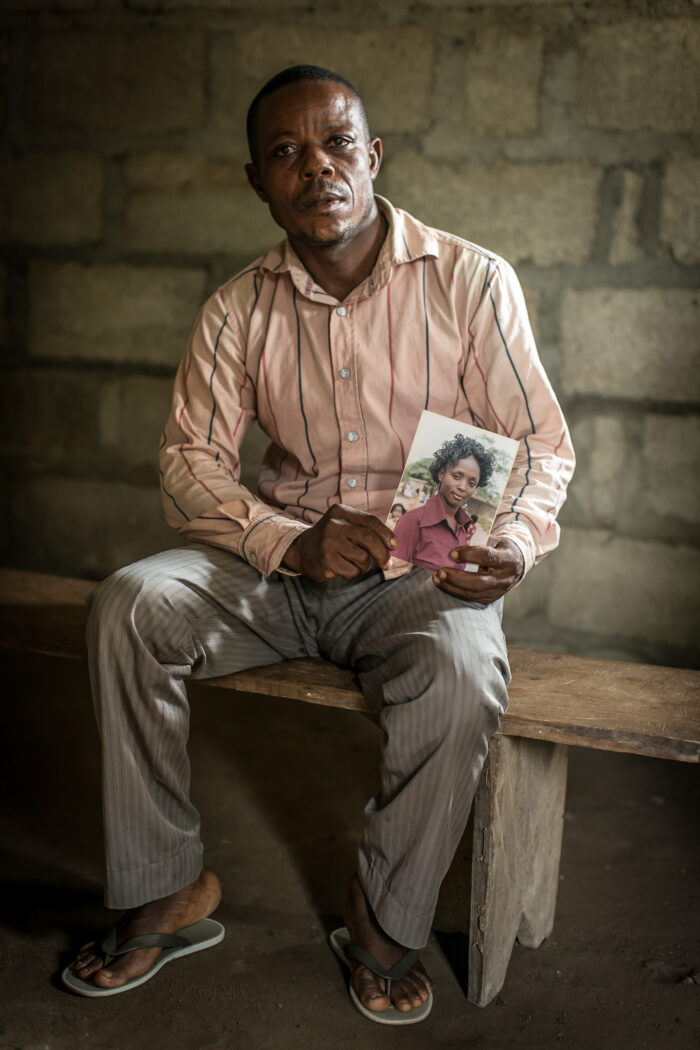

- Leverage data and elevate patient voices to highlight the critical need for quality medicines to improve maternal health and spur demand for quality-assured medicines

- Build the capacity of country leadership and authority bodies to govern local supply chain systems across the public and private health sectors

- Implement a process to report ineffective or unsafe medicines to regulatory agencies for prompt removal from the healthcare system

- Establish and disseminate clinical practices guidelines on safeguarding quality medicines, including effectively training local healthcare workers on new clinical guidelines and regulations

- Utilize artificial intelligence for predictive surveillance and increase detection of low-quality medicines

- Invest in local private health businesses with services that help address challenges related to stock-outs and availbaility of medicines (e.g. emergency & medical delivery services)

Quality medicines are an integral part of ensuring delivery of quality maternal health care for all women. Calling out quality medicines as a key component of quality care is an essential step towards ensuring safer childbirth and reducing preventable maternal mortality and morbidity around the globe.

This post was written by: Jeffrey L. Jacobs, MIM, Director of Product Innovation & Market Access, MSD for Mothers; Temitayo Erogbogbo, MSc, Director, Multilateral Engagement, MSD, and Advocacy Lead, MSD for Mothers; Vivianne Ihekweazu, Managing Director, Nigeria Health Watch; and A. Metin Gülmezoglu, MD, PhD, Executive Director, Concept Foundation.