Accelerating progress towards ending preventable maternal and newborn deaths: A rallying call as we reach the midpoint on the Sustainable Development Goals

This week, the UN will host the Sustainable Development Goals Summit. As leaders prepare to convene to discuss how to accelerate progress towards transformative change, Shanti Mahendra and Federica Signoriello from Options Consultancy Services Limited reflect on their key takeaways from this year’s International Maternal and Newborn Health Conference. As they note, we know a lot about how to prevent maternal and newborn mortality and morbidity but stronger political commitment and investment is needed to reach the SDG targets.

When the Trends in Maternal Mortality 2000 to 2020 report was published at the start of this year, the big headline was that maternal mortality rates had remained stagnant in 133 countries. In the WHO Director-General’s own words, it made for a “sobering” reading. Of course, this headline leaves out critical details around global disparities related to maternal deaths, with sub-Saharan Africa accounting for approximately 70% of global maternal deaths in 2020.[1]

In May, policymakers, public health professionals, civil society, implementing partners and donors convened for the 2023 International Maternal Newborn Health Conference in Cape Town. This provided a timely opportunity to align on the causes and solutions to preventable deaths and to drive maternal and newborn health to the top of government agendas. As we reach the halfway point of the SDGs, we reflect on four key takeaways from the conference that will be critical to accelerating progress on ending preventable maternal and newborn mortality and morbidity:

1. We have country examples of key drivers for decreasing maternal and newborn mortality.

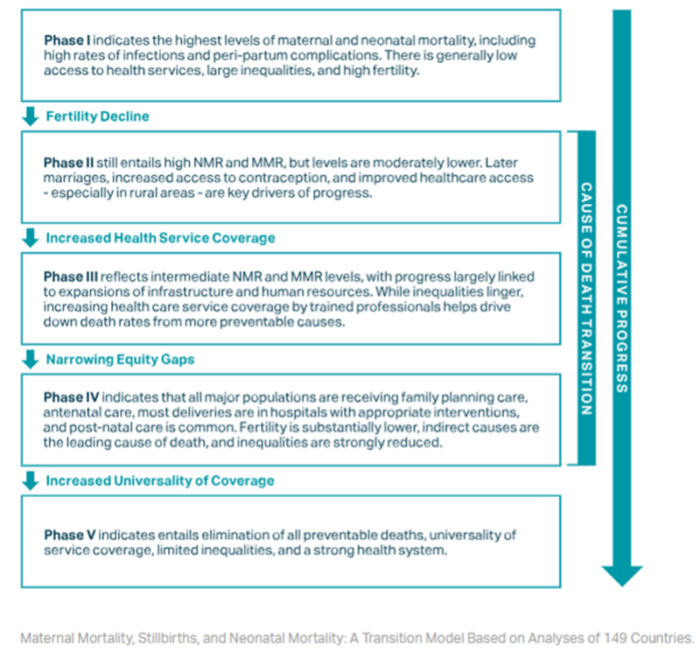

During the conference, Exemplars in Global Health presented on a transition model for maternal and newborn mortality, enabling benchmarking of countries and tracking progress across time. The model presents five phases of progress that a country can achieve, each characterised by performance on a set of indicators around fertility rates, access to facilities for birth and emergency care, levels of inequality and causes of death (e.g., infections versus obstetric complications).

Against this benchmarking, Bangladesh, Ethiopia, India, Morocco, Nepal, Niger and Senegal have progressed across one or two phases since 2000 and made significant reductions in maternal and newborn mortality. Four key drivers helped these countries progress, including:

- Increased contact with maternity services through expansion of services e.g., increased range, accessibility and availability of clinical services, removal of financial barriers and human resource availability.

- Better quality of care achieved by employing skilled cadres who were trained on clinical and respectful care, providing better content of services (in line with national or WHO guidelines and protocols), making supply chain improvements to ensure staff have the correct tools and commodities on hand, emphasizing use of data and introducing explicit quality of care policies. Providing specialized training to staff equips them with advanced knowledge, skills, and expertise, which allows them to make informed decisions and perform their duties effectively.

- Fertility declines and safer abortion practices achieved through increasing contraceptive use, later marriage, improved women’s education and labour force participation, and less restrictive abortion laws.

- Proactive governments demonstrated through strong policy commitment, legislation, improved resources for health, routine and regular use of information in decision-making and a flexible, adaptive and learning culture within government.

In Nepal, the combination of these four key drivers brought about a marked decline in maternal mortality by 70% between 1997 and 2021. Over the past 25 years, Options has worked side-by-side with the government through the Nepal Health Sector Support Programme, to support the achievement of ambitious national targets. Significant contributors to this have been the results based financing program – Aama Surakshya Yojana – which has helped improve access to institutional childbirth services; a clinical mentoring program for skilled health birth attendants; visiting service providers who help women in remote locations access contraception; and transformative policy vision as articulated in the Safe Motherhood and Newborn Health Plan.

2. Quality

Coverage is not enough to tackle preventable deaths. We need quality services. But this is not just ticking the boxes. It goes all the way to how the mothers feel about the service.

Queen Dube, Chief of Health Services, Malawi

Although significant progress has been achieved with making services accessible, the hardest journey is the one that is yet to be made; the main thrust of health systems now has to be on improving the quality of services. A good example of this is in Kenya, where in the midst of impressive national access statistics, sub-national and facility health teams, supported by the MANI-QC program, have also been able to improve quality of care. In Nandi, Kericho, Mombasa and Kwale counties this improvement has been evidenced through increased facility readiness to provide emergency, obstetric and neonatal care (EmONC) signal functions, improvements in the skilled birth attendance rate and reductions in the number of stillbirths. This progress was achieved through the following mechanisms:

- Training teams to conduct quarterly assessments of facilities’ readiness to perform EmONC life-saving signal functions.

- Collaborating with country health management teams to design and deliver a low-cost EmONC skills mentorship scheme to healthcare workers to enhance their expertise and competencies.

- Strengthening the reporting and review of the number and causes of death among mothers and babies to identify areas for improvement.

- Using data effectively to inform planning and resource allocation to address the factors that contributed to these deaths.

- Providing technical assistance around human resources for health, health information management systems and health financing.

Ensuring “quality” in healthcare is of vital importance, encompassing not only the provision of care but also the overall experience of users. Within this, midwives are the lynchpin who serve the goals of quality both in terms of provision as well as experience of care. A good example of ensuring quality is from experiences with midwife-led birthing centres (MLBCs) in Bangladesh, Pakistan, South Africa, and Uganda. This model of care not only improves outcomes for the mothers and babies but also is a cost-effective model for the system, as it allows decongestion of overcrowded hospitals by providing care for uncomplicated births and resource re-allocations to other quality improvements.

3. Government Stewardship and Multisectoral /Multi-stakeholder Collaboration is critical

A recurring theme throughout IMNHC 2023 was that strong leadership and vision is essential and must be backed up by adequate resources. This is even more important as the risk to health becomes greater from the impact of climate change and other global health security issues. Within decentralized settings, the main action in addressing maternal and newborn survival issues should happen at the sub-national/local levels and each context should tailor proven interventions to their specific needs. However, federal/national governments must provide stewardship to the sub-national level so that any gains made so far are not lost, and progress is equitable across the country. Stakeholders at the local and sub-national level (within the government and outside of it) need to be empowered and their voices heard in the planning and implementation of services. To achieve this, programmes can help facilitate multi-stakeholder accountability mechanisms. An example of such a mechanism is E4A-MamaYe, which brings together different actors to review the evidence around emerging and ongoing issues, discuss solutions and monitor implementation. These have proven success in fostering collaboration and joint planning between communities, civil society, health providers and government.

4. Listening to clients and person-centered care are essential to informing service delivery

Person-centred care which responds to each individual’s unique needs is essential for building trust in the system and encouraging women and families to seek the right care. During the conference many women, including Treasure, shared their personal stories of seeking care and how they were treated in the midst of unimaginable distress as they lost a baby.

These stories are essential for informing how ‘quality services’ are conceptualised and delivered. To achieve this, professional as well as citizens networks and alliances such as parent networks (e.g., International Stillbirth Alliance, CSO coalitions, Midwifery Associations) need to be empowered so that their representation in key decision-making spaces is improved. Key resources in support of this, include the launch of the Global Advocacy and Implementing Guide for Preventing and Addressing Stillbirths Along the Continuum of Care and the Parents Voices Initiative Registry of Stillbirth Support Organisations and Individuals.

The SDG Summit is billed as an opportunity to “reignite a sense of hope, optimism and enthusiasm for the 2030 Agenda”. As world leaders convene, it is important that the knowledge and inspiration gained and the commitments made earlier this year at the IMNHC conference are not lost and that investing in maternal and newborn health is recognized as essential.

[1] WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, World Bank Group, UNDESA: Trends in Maternal Mortality 2000-2020.