Tracking Progress in Mortality Reduction in Humanitarian Settings

Humanitarian needs are at an all-time high. Approximately 274 million people, or one in 29 people worldwide, are in need of humanitarian assistance. This is a 250% increase from 2015, when approximately one in 95 people worldwide were in need of humanitarian assistance. i Although the scale and nature of crises vary from country to country, it is widely recognized that we will not reach SDG, EPMM or ENAP targets without investment in these settings.

What ‘counts’ as a humanitarian setting?

For the purposes of this blog, we define countries affected by humanitarian crises as those with a current humanitarian response plan or funding appeal issued by the UN Office for Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UN OCHA). This is a subset of all countries affected by armed conflict, severe food insecurity, extreme weather events, and public health emergencies, but is an objective and widely recognized way of identifying countries who are unable to respond to resulting population needs and have appealed for international support.

What proportion of the global mortality burden can be associated with humanitarian settings?

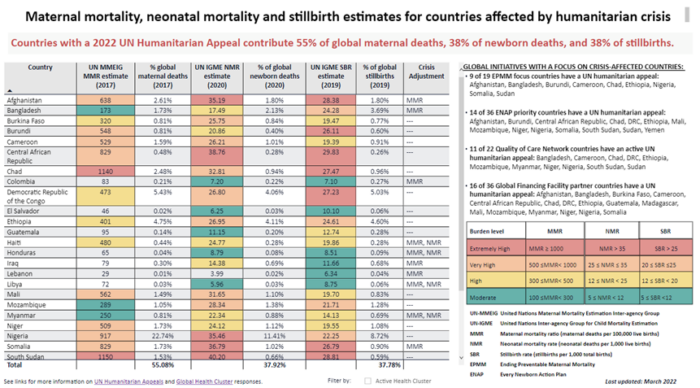

According to the most recent UN estimates, 55% of global maternal mortality, 38% of neonatal mortality and 38% of stillbirths occur in the 30 countries with a 2022 UN humanitarian response plan or regional response plan. ii, iii, iv, v

Figure 1: AlignMNH Mortality in Humanitarian Settings Dashboard

This does not necessarily mean that more than half of all maternal deaths and more than a third of newborn deaths and stillbirths occur in the geographic areas of these countries most directly affected by conflict, disease outbreaks and food insecurity. For example, the most recent UN estimates indicate that approximately 23% of all maternal deaths and 11% of all neonatal deaths occur in Nigeria. The country is now in its 9th consecutive year of humanitarian appeals, but not all of Nigeria is considered a humanitarian setting. In fact, the UN humanitarian response plans focus on only three (Borno, Adamawa & Yobe) of Nigeria’s 36 states, which the most recent census suggests are home to approximately 5% of the national population. vi Other densely populated areas of the country with poor quality of care may also be major contributors to the national mortality burden.

That said, we know that mortality risks are not evenly distributed across a country’s population. Women’s and children’s mortality risk (from non-violent causes) increases substantially with proximity to armed conflict, vii and understanding the extent to which affected populations are or are not considered in mortality estimates is important for tracking progress toward global and national development goals.

How do crisis-affected countries track progress towards global targets for mortality reduction?

The main data sources for tracking progress in mortality reduction in countries affected by crisis are the same as those used in countries that have not appealed for international humanitarian assistance. Although there are efforts underway to strengthen country health information systems (HIS) and civil registration and vital statistics (CRVS), household surveys are the most common sources used for national program planning and development progress tracking. viii However, not all countries conduct surveys on a regular basis. Because of the gaps and inconsistencies in information available for many countries, UN agencies and academic institutions use statistical modeling to produce comparable health statistics across countries that can be used to track progress towards global develop goals and produce regional and global estimates. ix Although much has been published on the strengths, limitations and improvements in both methods for estimation and transparency of reporting in recent years, x there has been less attention to the uncertainty surrounding estimates in crisis-affected countries, or how to meaningfully track progress during years where health systems are disrupted at a national or subnational level.

Household surveys

Only 16 of the 30 countries with a 2022 Humanitarian Appeal published a survey-based maternal mortality estimate in the last 10 years, and 21 of 30 published a survey-based neonatal mortality estimate during the same time period. The average time elapsed since publication of the most recent maternal mortality survey is 7.5 years and average time elapsed since publication of the most recent neonatal mortality survey is 5 years.

In some cases, the most recent national mortality survey pre-dates the escalation of conflict. For example, it is difficult to imagine that with only 50% of health facilities in Yemen functioning in 2018-2019, xi after five years of war, that the 2013 DHS still provides an accurate picture of health in the country. Similarly, it would be unreasonable to infer any insights on the current state of population health in Syria based on the 2009 Family Health Survey supported by the Pan Arab Project for Family Health.

In other cases, surveys conducted before, during and after conflicts and can provide insights on national trends in health service coverage and outcomes.xii Although deviations from planned sampling strategies due to insecurity or other access constraints are not likely to have an impact on the reliability of national estimates unless more than 10% of the sample is affected; such deviations, as well as the exclusion of internally displaced populations from sampling frames, could significantly impact reliability of subnational estimates. xiii

Statistical modelling

The World Health Organization and United Nations Children’s Fund, in collaboration with other UN agencies and academic experts, regularly use statistical modeling techniques to update estimates for key indicators such as mortality rates and causes of death. Sophisticated statistical analysis techniques are used to predict levels and trends in mortality based on past survey, census and vital registration data and other key indicators such as country GDP, fertility rate and the proportion of live births with skilled health personnel. The strength of these estimates is that they provide consistent comparable data across countries, which is particularly valuable for tracking progress towards global targets. Teams developing UN estimates are very transparent about the data sources and methods used, and note in each report that the methods used to account for impacts of armed conflict will be improved as data becomes available.

Using outdated and potentially non-representative data as model inputs and applying assumptions that might not reflect the reality of a complex conflict creates estimates that may be very misleading.

Kuehne & Roberts, 2021

It is important, however, to understand that modelled estimates are only as strong as their data inputs and accuracy of assumptions.

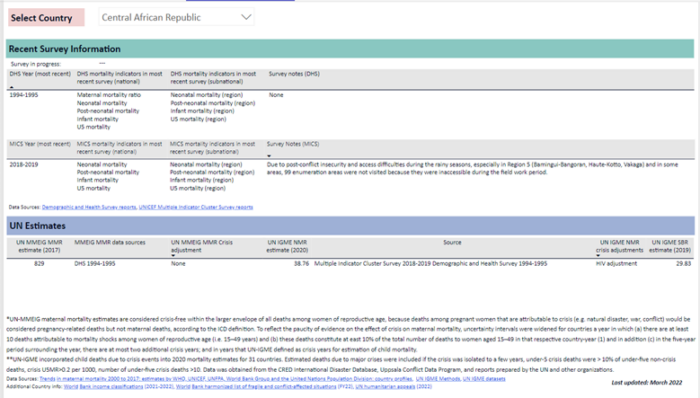

In a recent Conflict and Health editorial, Anna Kuehne and Leslie Roberts provide a vivid illustration of the challenges of relying on modelled UN estimates in a conflict affected country like the Central African Republic where estimates are predictions based on a DHS in 1994 and MICS in 2018, and show a steady decline in mortality rates even through years the country endured a brutal civil war. xiv

Where can I find the most recent mortality estimates for crisis-affected countries?

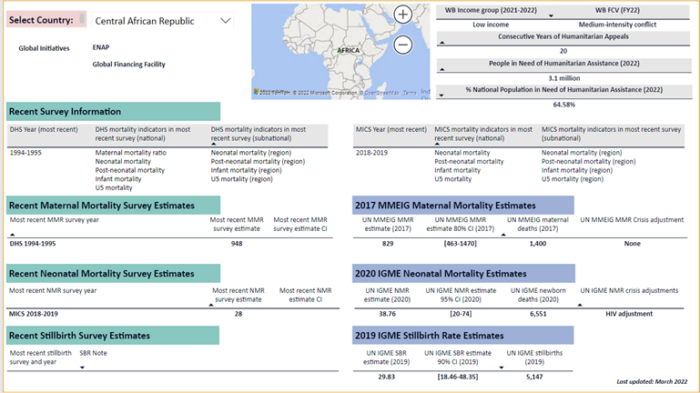

The Mortality in Humanitarian Settings Dashboard is a tool for stakeholders working in countries affected by humanitarian crises to identify and compare the most recent maternal mortality, stillbirth and neonatal mortality burden estimates from national household surveys and global modelling exercises.

Figure 2: Sample Country Profile

Country profiles present the most recent national survey and modelled mortality estimates, as well as available notes on sampling strategy adjustments for household surveys and data sources used in statistical modelling.

Figure 3: Sample Methodological Notes

Selection of the ‘best available’ data source for a given purpose must be made on a case-by-case basis, and extra caution taken when making decisions based on mortality estimates for crisis-affected countries.

Improving data for action

As highlighted at the AlignMNH Opening Forum in April 2021, a comprehensive approach is essential for reaching the SDG, EPMM and ENAP targets for mortality reduction by 2030, and data play an instrumental role in driving progress. Steps that can be taken to better assess the impact of crises on progress towards mortality reduction targets include:

- Tracking ENAP and EPMM coverage targets and milestones at a national and subnational level

- Routinely reviewing and triangulating health service coverage data (from surveys and routine health information systems), and conducting routine data quality assessments

- Engaging stakeholders in crisis-affected areas in interpretation of data on health service coverage and quality in relation to population trends and health service disruptions

- Sharing lessons learned within and across countries

What do you see as opportunities for improving data availability, quality and use for tracking progress towards global and national targets? Join the April 2022 Collective hosted by AlignMNH to share your thoughts and learn about other ways to engage on the road to the International Maternal Newborn Health Conference to be held in Cape Town, South Africa in May 2023.

*Hannah Tappis is a Senior Technical Advisor at Jhpiego and Maternal and Newborn Health Sub-Working Group co-chair for the International Working Group on Reproductive Health in Crises

*Emily Bryce is a Monitoring, Evaluation & Learning Advisor at Jhpiego.

*Ties Boerma is a Professor for Community Health Sciences at the University of Manitoba.

References

[i] Global Humanitarian Overview 2022

[v] https://fts.unocha.org/appeals/overview/2022

[vi] https://gho.unocha.org/nigeria

[vii] Bendavid E, Boerma T, Akseer N, Langer A, Malembaka EB, Okiro EA, Wise PH, Heft-Neal S, Black RE, Bhutta ZA; BRANCH Consortium Steering Committee. The effects of armed conflict on the health of women and children. Lancet. 2021 Feb 6;397(10273):522-532. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00131-8. Epub 2021 Jan 24. PMID: 33503456.

[viii] Carla AbouZahr, Ties Boerma & Daniel Hogan (2017) Global estimates of country health indicators: useful, unnecessary, inevitable?, Global Health Action, 10:sup1, DOI: 10.1080/16549716.2017.1290370

[ix] Boerma, T., Mathers, C.D. The World Health Organization and global health estimates: improving collaboration and capacity. BMC Med 13, 50 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-015-0286-7

[x] Global Health Action, 10: supp1

[xi] https://healthcluster.who.int/publications/m/item/yemen-herams-dashboard-2018—2019

[xii] Boerma T, Tappis H, Saad-Haddad G, Das J, Melesse DY, DeJong J, Spiegel P, Black R, Victora C, Bhutta ZA, Barros AJD. Armed conflicts and national trends in reproductive, maternal, newborn and child health in sub-Saharan Africa: what can national health surveys tell us? BMJ Glob Health. 2019 Jun 24;4(Suppl 4):e001300. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2018-001300.

[xiii] Ibid.

[xiv] Kuehne, A., Roberts, L. Learning from health information challenges in the Central African Republic: where documenting health and humanitarian needs requires fresh approaches. Confl Health 15, 68 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13031-021-00405-1