Overcoming the Silence around Stillbirth

Every 16 seconds, a family loses a child to stillbirth. The months they spent planning for their baby, feeling the baby grow and move, imagining their family’s future—cut short, and often without explanation from a health system ill-equipped to provide the respectful, compassionate bereavement care families deserve.

Acknowledging that these babies were born is key, yet stillbirth is rarely discussed or explained. Stigma, taboo, and misconceptions around these deaths lead to silence at all levels, from parents experiencing grief, shame, and confusion about what happened; to health care providers who lack the tools to support parents after this devastating loss; to the community, which shares in the family’s grief yet is unsure how to respond; to the health system, which often neglects to record the stillbirth as a death and thus fails to acknowledge the birth.

If we don’t count these deaths, we can’t address them to prevent future deaths. And to consistently and accurately count stillbirths so that countries can measure their progress against global targets, we need to start acknowledging that they are deaths. Ask any family whose baby was stillborn—their loss was a death. Stillbirths must similarly be recognized as deaths in the health system.

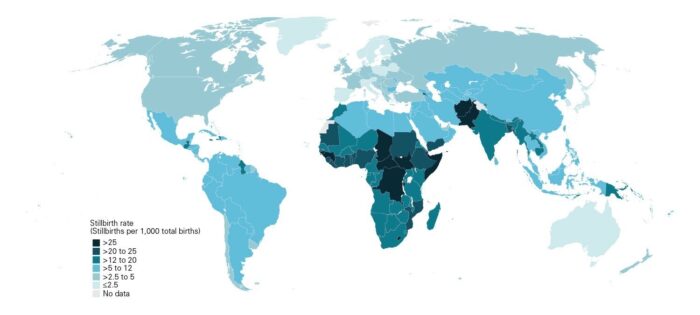

Although stillbirth rates reflect quality of care more than income level, stillbirth disproportionally affects low- and middle-income countries. About three-quarters of stillbirths occur in sub-Saharan Africa and Southern Asia, nearly half during labor. Most of these deaths are preventable—often through quality antenatal care. Yet, despite 48 million such deaths in the past 20 years, stillbirths are largely absent from worldwide reported data. Sixty-two countries, and more than 40% of countries in sub-Saharan Africa, have no stillbirth data or quality data available. Clearly, we need robust, reliable systems to track maternal and newborn mortality and stillbirths—critical measures of quality of care and health systems strength.

But beyond data, we need parents to talk about their experience during pregnancy, labor, and delivery of their stillborn child. Without parent voices, we’re limited in the amount of change we can make through research studies.

We must ask: How will parents talk about it, if no one talks to parents about it?

Often there is so much happening during delivery that no one explains to the parents what is going on until the baby is born stillborn. Health care providers may assume that the parents don’t want to talk about it, and don’t want to see their baby. In fact, many parents do want to talk about the death and do want to hold their baby, but because of these assumptions they are not given the option. Explaining what happened to their child gives parents the courage to talk about the stillbirth.

At the AlignMNH Opening Forum session “Stillbirth: Data and Parent Voices to End Preventable Death”, Still a Mum founder Wanjiru Kihusa stressed the importance of providing information and compassionate care to parents and families: “Speak to parents and let them know what is going on. Even if you can give information beforehand so they can decide what to do. Do they want to see their baby, do they want to hold their child? Those are the decisions they can make if you give them the relevant information. Do not remove that right from them.”

Health care providers need to be equipped with the skills and tools to talk to parents and support them through the grieving process. The community, too, needs information so that they can support these families in crisis, and we can start closing the gap between stillbirth rates and targets. Efforts are being made to overcome the reluctance of health care workers to give parents the information they want about their stillborn child and help them through the grieving process. The International Stillbirth Alliance aims to drive global change for the prevention of stillbirths and newborn deaths by focusing on parent-centered, parent-driven care during pregnancy and before and after a death. Through the Parent Voices Initiative, the International Stillbirth Alliance is developing a toolkit to help start conversations about stillbirth. Health care providers can use the toolkit to integrate grief counseling and bereavement support into maternal health care practices and learn how to explain the circumstances around a stillbirth. A draft toolkit is being piloted for providers in India; and Still A Mum, a parent-focused organization in Kenya, is piloting the toolkit with parents and grief counselors.

Meeting global targets for prevention of stillbirth by 2030 will require more than research and programmatic studies and country-level efforts. It will require raising parent voices and strengthening resolve across the health system to acknowledge, recognize and record each stillbirth as a death—as a family’s loss of a daughter or son and dreams for the future cut short.

Rakhi Dandona, PhD is Professor at the Public Health Foundation of India, National Capital Region, India and Professor of Health Metrics Sciences at the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, University of Washington, Seattle, USA. She is also a board member of the International Stillbirth Alliance.